| |

|

Wagner

Society of Dallas

Invites you to a

MATINEE CONCERT

"Richard Wagner and the Ritter Viola"

"Ritterbratsche"

Saturday, March 26, 2005, 2:30 pm

4808 Drexel Drive - Dorothea Kelley "Concert Hall"

PROGRAM:

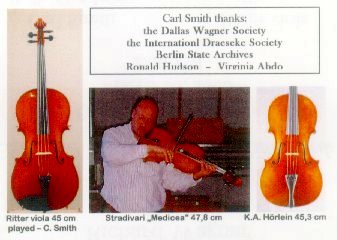

Carl Smith - Ritter Viola & Bella Gutshtein

- Piano

Carl Smith was born in Binghamton, NY,

where he

began violin studies at the age of 5. As a student, he took part

in international chamber music tours. In 1976, he studied with

Nadia Boulanger at Fontainbleau, France, and thereafter with

Scott Nickrenz in Boston. Since 1978, he has been a member of the Graz

Philharmonic Orchestra, and the Natal Philharmonic Orchestra

in Durban, South Africa. In 2001, he transferred to the Ritter

Viola, and has been touring

as a soloist on the "Ritter Viola".

Bella Gutshtein was born in St.

Petersburg, Russia. Her piano studies were at the St. Petersburg

Conservatory. She is a faculty member of the AIMS Summer Music

program in Graz, Austria. She is founder of the Russian Cultural

Society in Naples, Florida, where she lives.

You may contact Carl Smith directly at the address below.

Carl Smith

Bergmanngasse 15

A-8010 Graz

Austria-Europe

Tel:Fax: +43-316-817683

csmith@netway.at

WSD President

Roger Carroll Makes Announcements |

Virginia Abdo Presents Program Notes about

the Ritter Viola |

Carl Smith and the Ritter Viola, with Bella Gutshtein at

the Piano |

Tuning |

Playing |

Bella Takes a Solo Bow |

WSD Treasurer

Greg McConeghy |

Ron Hudson

Concert Sponsor |

A Good-Sized Audience Assembles after Intermission |

Greeting Audience |

Interested Questioners |

Carl Smith Explains |

Bella Gutshtein |

An Interesting Gift |

David Morgan

and Kyle Kerr |

|

|

|

| Light

Refreshments after the music |

Photos for WSD by Ed Flaspoehler - Click on

Images for Enlarged View

Richard Wagner

and the Ritter Viola

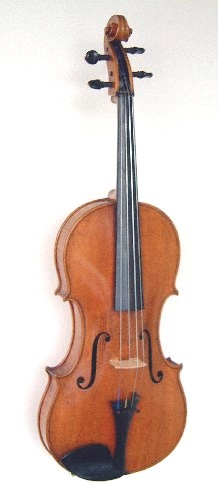

The term, "Ritter viola", refers to the violist and music

author Hermann Ritter. Ritter was born on September 16, 1849 in

Wismar, Germany, and died on January 25, 1926. In 1865, Ritter

began violin studies at the "Neuen Akademie der Tonkunst" (New

Academy of Tonal Art) in Berlin. He studied there until 1870,

giving lessons to finance his education. He studied there for a

short time with Joseph Joachim. In 1870, he became a member of

the Court Ensemble in Schwerin for two years, followed by the

position as conductor of the Heidelberg City Orchestra. He

retired shortly from this position to study music and art

history and philosophy in Heidelberg University. During these

studies, he turned to the viola, with the aim to equal its tone

to that of the violin and cello. In his study of the development

of stringed instruments, he stumbled across the manuscript

"Geometric Principles of Violin Making" by Antonio Bagatella,

printed 1782 in Padua, Italy. According to these principles, he

commissioned the Wurtzburg violinmaker, Karl Adam Hoerlein

(1824-1902), to build him a "Viola alta", as he termed it. Most

likely from a recommendation of Professor Ludwig Nohi, with whom

Ritter had studied music history, he was invited to Bayreuth. The term, "Ritter viola", refers to the violist and music

author Hermann Ritter. Ritter was born on September 16, 1849 in

Wismar, Germany, and died on January 25, 1926. In 1865, Ritter

began violin studies at the "Neuen Akademie der Tonkunst" (New

Academy of Tonal Art) in Berlin. He studied there until 1870,

giving lessons to finance his education. He studied there for a

short time with Joseph Joachim. In 1870, he became a member of

the Court Ensemble in Schwerin for two years, followed by the

position as conductor of the Heidelberg City Orchestra. He

retired shortly from this position to study music and art

history and philosophy in Heidelberg University. During these

studies, he turned to the viola, with the aim to equal its tone

to that of the violin and cello. In his study of the development

of stringed instruments, he stumbled across the manuscript

"Geometric Principles of Violin Making" by Antonio Bagatella,

printed 1782 in Padua, Italy. According to these principles, he

commissioned the Wurtzburg violinmaker, Karl Adam Hoerlein

(1824-1902), to build him a "Viola alta", as he termed it. Most

likely from a recommendation of Professor Ludwig Nohi, with whom

Ritter had studied music history, he was invited to Bayreuth.

Ritter meets Richard Wagner

Wagner receives Liszt in the Villa Wahnfried

Hermann Ritter present

Richard Wagner was constantly in search of new tonal colors,

especially in the mid-register. Therefore, the viola developed

by Hermann Ritter was highly welcomed by him.

Wagner's special interest in strong mid-register instruments

is well known. In 1875, he prescribed in his works in place of

the English born an "Alt-Hoboe", which was constructed by the

instrument maker Stengel, according to Wagner's instructions.

This instrument had a larger bore size than the English horn.

Its sound bell had the shape of a pear, in contrast to the

normal English horn. Cosima Wagner remarked in her diary,

February 9, 1876: "Mr. Ritter, from Heidelberg, is bringing a

new type of viola, which Richard finds excellent and wishes to

introduce into his orchestra".

Ritter described his meeting with Wagner in his work,

"Richard Wagner and the Inventor of the Viola alta", with the

following dialogue: "The guests arrived and he announced that I

would present and perform on a better tone-developed viola. I

should play 'something, which you can demonstrate all the

strings'. He said further, 'Fischer will accompany you on the

piano'.

"I chose Wolfram's Fantasy from Tannhauser and was

accompanied by the now famous Court Conductor, Franz Fischer. As

I finished, the Maestro tapped me on the shoulder and said:

‘Your instrument sings wonderfully! It's a shame I wasn't

familiar earlier with it. What all I could have written in the

orchestra for it! Incidentally, you are not a candidate for

philosophy, but rather a true musician. Remain with your art and

let the doctor title go! What need does a musician have for a

doctorate?'

"Pointing to my Viola alta, Wagner stated, 'The correct alto

voice! I know several beautiful pieces for your instrument from

the sonatas for violin and harpsichord by Bach which lay heavily

in the mid-register. Could six such Altviolins of your

construction be included in the Festival Orchestra?' I answered,

'Surely, Maestro, if persons can be found, thatwould play them.'

- 'I will speak with Thoms in Munich.'

"Later, as Wagner spoke in my presence with this violist from

the Munich Court Theatre Orchestra, he asked, 'Why can't we have

more Ritter Altviolins?' Answered Thoms, ' Yes, Maestro, it's

difficult. It could be done but we'd have to learn!' "

Later, Wagner wrote Ritter a tong letter with the following

script and engaged him as solo violist for the Bayreuth Festival

Orchestra:

Respected Sir! I am truly sorry still not to have sufficient

time to deal with your Altviolin at the length I feel noteworthy

and to lend my support in giving this instrument it's earned

respect. I am convinced that the general introduction of the

Altviolin in our orchestras is not only the intentions of

composers, who, up to now, intending the voice of the true

Altviolin sound but having to make do with the normal voila,

which can now be put into rightful perspective and which will

also bring about a meaningful and advantageous change of the

whole treatment of the stringed instrument quartet, The free

A-string of this no-longer thin and nasal sounding, but rather

bright and good-sounding instrument, will replace the reserved

middle four string of the violin with an energetic voice, as the

violin has been limited so much in its energetic projection of

sound in this register, that Weber here, for example, very often

had to add a wind instrument (clarinet or oboe) for support. The

Altviolin makes this no longer necessary and the composer

doesn't have to make use of mixed colors where the pure string

character was the intention. Now it is hoped for, that this

greatly improved instrument be immediately distributed among the

best orchestras and the best violists be quickly urged to give

it serious treatment. We must be prepared here for great

resistance, as unfortunately the majority of most of the

orchestra violists are not at the height of string

instrumentalists.

A hearty initiative will attract followers, whose example

will quicken conductors and administrators. I regret you have

brought this affair to me so late and that,, especially at this

time, being so busy, I have not been able to do as much as

possible in this short time, I request to be informed regarding

the attention of your instrument by the respected court musician

Thoms in Munich. My friend, Fleischhauer (concertmaster in

Meiningen), has already stated his willingness to recommend the

Altviolin for the upcoming festival in Bayreuth. Having the

possibility to have at least two of these instruments played in

my orchestra, I regret not being able to already have six of

them. It appears to be impossible.

I request exact information about what success has been

attained and that you make unrestricted use of me and my

recommendation in your cause.

I thank you for your most interesting and informative

treatise and remain respectfully at your service

Richard Wagner.

Bayreuth, March 28,1876

Wagner did, in fact, eventually have six Ritter violas in his

orchestra.

Berlioz was also not pleased with the sound

of the viola in his day, which is documented by his following

statement:

Here it must be said that most of the violas at present in

our French orchestras have not the necessary dimensions. They

have neither the size, nor as a natural consequence the tone

power, of a real viola; they are mostly violins strung with

viola strings. These Musical Directors should absolutely forbid

the use of these bastard instruments, whose tone deprives one of

the most interesting parts in an orchestra of its proper color,

robbing it of all its power, especially in the lower registers.

In the following years, Hermann Ritter had great concert

success, and the Ritter viola, as it was commonly referred to,

began to break through.

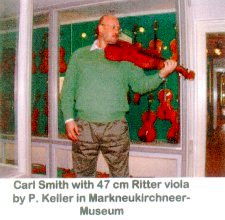

When the violinmaker, Hoerleln, died, Philip Keller acquired

the moulds in 1902. He was authorized by Prof. Ritter to build

this viola and also developed the 5-string Ritter viola. The

Ritter viola in the instrument collection of the Munich City

Museum bears the label:

"Viola alta (Altgeige)

nach Modell Prof Hermann Ritter

Autorisierter Verfertiger: Phil. Keller Atelier fdr Geigenbau

und Bogen

1906 Wurtzburg, gegr. 1832 Nr. 95 ".

"Ritterbratsche"

Following Ritter's Death,

The Instrument was

Forgotten

Following the death of Hermann Ritter in 1926 it became quiet

regarding the Ritter viola. In 1929, when the viola society put

out the question, asking "Who still plays the Ritter viola?",

only one former student of Ritter, the concertmaster from

Elberfeld, Karl Paasch, replied, "I am a former student of

Professor Ritter and I gladly play the Ritter viola as a solo

instrument. I also play it in the orchestra when its character

deems proper, specifically for particular solos with great tone,

such as: Harold symphony - Kaminski Magnificat - Tristan solos

in Bayreuth - H. Wolf. Italian Serenade, etc. Occasionally, I

arrange to have a normal and a Ritter viola in the orchestra and

switch between them both."

The Royal Saxon Chamber Virtuoso, Alfred Spitzner, replied

similarly in his authored title, "The Viola in Word and

Picture": "Ritter rightfully states that it is completely false

to produce a nasal tone from the viola in normal fashion. He

attempted to help this situation with his improvement of the

Viola alta. There are, in fact, a few good old violas that are

not nasal. Unfortunately, the dimensions of the Ritter viola are

so disadvantageous, that they are very strenuous for a player

that does not have long arms and fingers, especially in the case

of our present-day composers. To ease these dimensions, Ritter

newly added an additional 5th E string."

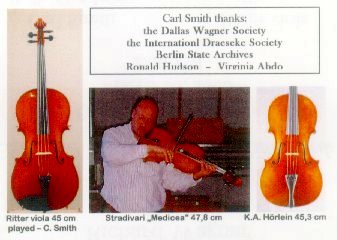

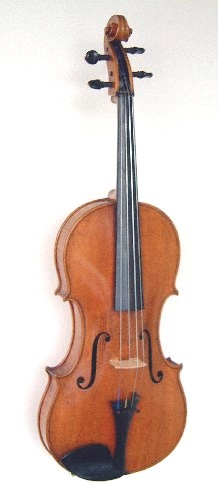

In fact, the size of the Ritter viola does not make it easy

to play. While normal violas have a body length of 37-42 cm,

measured across the top plate, the above-mentioned Ritter viola

in the museum has one of 45.3 cm with a complete length of 73.9

cm. The vibrating string length is 40.6 cm.

The 5-string Viola alta, which

also was built by Philipp Keller in Wurtzburg, was more

advantageous to violists. A 5-string Ritter viola in the City

Museum has a 2.7 cm shorter length of 71.2 cm, with a body

length of 43 cm. The vibrating string length of this instrument

is also 40.6 cm.

Herrmann Ritter imagined this

5-string viola for his idea of a string quartet, comprised of a

normal violin, the 5-string viola, a tenor violin an octave

lower than the violin and a cello. The composer, Felix

Weingartner, authored in 1905 a well-wishing article in the

magazine, "Die Musik". He made specific mention of the tone

characteristics of the mid-register instruments developed by

Ritter: "In the tonal function I noticed the penetrating

character

of the 2nd violin voice, due to that it was played on a viola

seated across from the violin, while the tenor violin's voice

was more pronounced to that of the cello and higher voices. More

tonal independency of the 'middle registers was, therefore, the

opinion of my observation. This is explained in that, while the

normal quartet being represented by three individualities, the

violin, viola and cello, we have here four completely separate

ones, in the true meaning of a quartet. A great tone production

goes hand in hand with a much darker tone color, having a

wonderful effect in certain passages, which is nevertheless

certainly not the overall intention of the composers."

Richard Strauss (I 864-1949) also

made mention of the 5-string Ritter viola in a footnote of his

1904 expanded and revised instrumentation treatise by Hector

Berlioz:

Prof Hermann Ritter from Wurtzburg built a 'Viola alta" which

has an additional higher-tuned 5th string in addition to the

normal four. The instrument portrays a much more pronounced tone

volume, due to its size and has, on the other hand, a very

usable higher pitch, due to the added fifth.

Its use today is unfortunately still very limited, which is

due to the fact, that the manual facilitation of the Ritter

viola requires a lot of physical strength; Players with short

arms and fingers should consider exchanging it for the more

comfortable normal viola.

Richard Strauss was practical enough to foresee the playing

difficulties of this large instrument. Ulrich von Wrochem from

Milano impressively demonstrated the characteristics of this

viola in a concert in the Munich City Museum.

It is suspected and remains to be explained whether the

viola/violin part of the solo violist in Strauss' opera,

"Elektra", was, in fact, actually intended for this 5-string

Ritter viola. - C. Smith

Dr. Gunther Joppig

Johannes

Brahms (1833-1897) viewed Felix Draeseke (1835-1913), along

with Anton Bruckner (1824-1896), as his main rival in the

symphonic and religious field of composition. At first this may

surprise us, but this reaction ends quickly when one listens to

the third symphony, bearing the title, "Symphonia tragica". Draeseke certainly did not have to hide behind his famous

contemporaries, even though he never received wide pubic

acclaim. In the field of experts this was not so. It was not

only Brahms who respected Draeseke. Personalities such as Hans von

Bulow, Arthur Nikisch, Fritz Reiner, Hans Pfitzner or Karl Boehm

also quickly recognized Draeseke's compositional qualities.

Nevertheless, this recognition did not gain wide-spread

acceptance of his music. Johannes

Brahms (1833-1897) viewed Felix Draeseke (1835-1913), along

with Anton Bruckner (1824-1896), as his main rival in the

symphonic and religious field of composition. At first this may

surprise us, but this reaction ends quickly when one listens to

the third symphony, bearing the title, "Symphonia tragica". Draeseke certainly did not have to hide behind his famous

contemporaries, even though he never received wide pubic

acclaim. In the field of experts this was not so. It was not

only Brahms who respected Draeseke. Personalities such as Hans von

Bulow, Arthur Nikisch, Fritz Reiner, Hans Pfitzner or Karl Boehm

also quickly recognized Draeseke's compositional qualities.

Nevertheless, this recognition did not gain wide-spread

acceptance of his music.

Revolutionary new ideas in the

beginning of the 20" century left Draeseke quickly behind and

forgotten. When one opens a common program guide, usually no

more than a couple lines of information about Felix Draeseke can

be found. For example: "Felix Draeseke (1835-1913), in light of

Schumann, Brahms and Liszt, stands at the gate of late

romanticism. Occasionally one hears his attractive Serenade D

major, op.49 (1988) or (from 4 Symphonies) the

Tragica, c minor,

op.40 (1886). His brilliant piano concerto (1886) and the violin

concerto (1881) are forgotten." (Reclams Konzertfuhrer,

15.Auflage 1994, S.924)

Dmeseke had a preference for the music of

Richard Wagner, as he himself gladly composed melodically

and was not afraid to use dramatic expression or effects. As a

critic, he supported the north German attitude, meaning, he

sided with Wagner and Liszt. This did not bring him the

affection of Johannes Brahms. Nevertheless, Brahms respected

Draeseke as a great composer. Otherwise, he would not have

considered him as a rival.

Draeseke met both Wagner and Liszt. Liszt's symphonic poetry

had as deep an effect on him as did Wagner's music. Personally,

however, he felt closer to Wagner, to whom he attributed great

closeness to the common man. It is this affection for Wagner

which has also led to the neglect of his works up to today.

Unfortunately, the National Socialists in Germany used Draeseke,

as well as Wagner, for their purposes. The closeness to the

people, dramatic characteristics, and influential gestures were

all too well suited for them to label Draeseke as a "Germanic"

composer. And so it came that Draeseke's biography in two

volumes appeared during the Third Reich under the title "The

Life and Passion of a German Master", by Erich Roeder.

From 1862-1876, Draeseke resided in Switzerland. Later, he

also traveled distantly. For example, in 1869, he traveled from

France to Spain, to North Africa and, lastly, to Italy. On this

trip, he composed the first of his four symphonies (op. 12),

which was premiered in Dresden on January 31, 1873, under the

direction of Julius Rietz. In it, Draeseke combined "The Music

of the Future " with "classical forms". His perception goes

toward the future as well as looking to the past. His critics

gladly overlooked this fact. His reported total admiration for

Richard Wagner is also only a half-truth. Draeseke said, "Of the

new composers, Wagner remains for me the most influential." But

he also said, "It took a long time until I could come to terms

with the maestro's (Wagner) late development, and I have to

admit I am still not sympathetic with certain peculiarities of

his later style, and do not like to see them copied or become

standard."

As stated, Wagner and Liszt played a large influence on

Draeseke. Now that he had composed three symphonies, it was he

who influenced younger composers. For example, Richard Strauss

(1864-1949), received ideas from Draeseke's symphonies. The "Tragica"

was premiered on January 13, 1888, under the direction of Ernst

von Schuch. In this period, Draeseke experienced his greatest

success, not only with his symphonies, but also with his other

works, such as, "Das Leben ein Traum" (Calderon) or "Penthesilea"

(Kleist).

After Draeseke's death, Arthur Nikisch promoted his works

further, especially the third symphony. Nonetheless, even he

could not hinder the waning interest of his works, which

eventually became all but forgotten. There were too many events

and musical developments occurring at the time.

One only has to consider such composers as

Stravinsky (,,Sacre du printemps", 1913) or Schoenberg. Only

now, at the beginning of the 21st century, does time appear

again to be ripe to open itself to Draeseke’s music, which has

suffered neglect under the wheels of so-called development.

Frau Brigitte Draeseke, great grandniece of Felix Draeseke,

with

Karin and Carl Smith at her arrival in Graz, Austria,

for a

Ritter Viola Concert

|

| |

Welcome to The Wagner Society of Dallas. You know, as Texans, we're

bound to strive for being the biggest and best of all the Wagner groups

in the world over.

My hope, in addition, is that we ensure your attendance and

participation by offering an interesting, stimulating, and enjoyable

array of meetings, recitals, and travel. Let us know if you have

suggestions for future activities, and do make an effort to join in

during the coming months with your membership, attendance, and above all

joy of being with fellow Wagner aficionados.

Roger Carroll

President of the Wagner Society of Dallas

The Wagner Society of Dallas - Virginia R.

Abdo and Dr. James T. Wheeler,

Co-Founders

The Wagner Society of Dallas is devoted to furthering the enjoyment

and appreciation of the music of Richard Wagner. The Dallas group is one

of many Wagner Societies all over the world. It is a non-profit

organization open to anyone who enjoys the works of Richard Wagner and

who would like to participate in the Society’s activities.

The Wagner Society of Dallas has monthly meetings and programs which

feature recitals, lectures, video screenings, receptions for opera

singers and personalities, and trips to Wagner performances in other

cities. We welcome music lovers who are already familiar with Wagner’s

works as well as those who may want to become more knowledgeable about

Wagner’s music.

Member Benefits include attendance at programs, our newsletter,

discount on books and CD’s, advance notice of events and selected ticket

services, receipt of the Membership Directory, ticket allotments to

Bayreuth, and an active link with fellow Wagnerians throughout the

world. |

|

The term, "Ritter viola", refers to the violist and music

author Hermann Ritter. Ritter was born on September 16, 1849 in

Wismar, Germany, and died on January 25, 1926. In 1865, Ritter

began violin studies at the "Neuen Akademie der Tonkunst" (New

Academy of Tonal Art) in Berlin. He studied there until 1870,

giving lessons to finance his education. He studied there for a

short time with Joseph Joachim. In 1870, he became a member of

the Court Ensemble in Schwerin for two years, followed by the

position as conductor of the Heidelberg City Orchestra. He

retired shortly from this position to study music and art

history and philosophy in Heidelberg University. During these

studies, he turned to the viola, with the aim to equal its tone

to that of the violin and cello. In his study of the development

of stringed instruments, he stumbled across the manuscript

"Geometric Principles of Violin Making" by Antonio Bagatella,

printed 1782 in Padua, Italy. According to these principles, he

commissioned the Wurtzburg violinmaker, Karl Adam Hoerlein

(1824-1902), to build him a "Viola alta", as he termed it. Most

likely from a recommendation of Professor Ludwig Nohi, with whom

Ritter had studied music history, he was invited to Bayreuth.

The term, "Ritter viola", refers to the violist and music

author Hermann Ritter. Ritter was born on September 16, 1849 in

Wismar, Germany, and died on January 25, 1926. In 1865, Ritter

began violin studies at the "Neuen Akademie der Tonkunst" (New

Academy of Tonal Art) in Berlin. He studied there until 1870,

giving lessons to finance his education. He studied there for a

short time with Joseph Joachim. In 1870, he became a member of

the Court Ensemble in Schwerin for two years, followed by the

position as conductor of the Heidelberg City Orchestra. He

retired shortly from this position to study music and art

history and philosophy in Heidelberg University. During these

studies, he turned to the viola, with the aim to equal its tone

to that of the violin and cello. In his study of the development

of stringed instruments, he stumbled across the manuscript

"Geometric Principles of Violin Making" by Antonio Bagatella,

printed 1782 in Padua, Italy. According to these principles, he

commissioned the Wurtzburg violinmaker, Karl Adam Hoerlein

(1824-1902), to build him a "Viola alta", as he termed it. Most

likely from a recommendation of Professor Ludwig Nohi, with whom

Ritter had studied music history, he was invited to Bayreuth.